World Information

Excellence in Hand Hygiene Begins Where Strategy, Leadership, and Culture Come Together

A HosCom International 2020 Vol. 1 Article

Authors:

Alexandra Peters, MA, PhD Candidate & Prof. Didier Pittet, MD, MS, CBE

Infection Control Program and WHO Collaborating Centre on Patient Safety, The University of Geneva Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland

Everyone knows that hand hygiene is vitally important in healthcare, but to date, no one has figured out how to achieve optimal compliance. How does one achieve excellence in hand hygiene? In order to analyze this question, one must first understand the nature of “excellence” and its components, as well as the context that makes hand hygiene so deceptively simple and intuitive as an intervention, but so complex and difficult to implement successfully. This paper will look at available tools for improvement and implementation, as well as key case studies and examples that help to illustrate the qualitative aspects of the field.

Healthcare-associated infection is known for being one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality, and the most frequent adverse event in healthcare worldwide1. It has long been recognized that improved compliance with hand hygiene drastically reduces healthcare-associated infections2. More recently, the pivotal role of preventing healthcare-associated infections in combating antimicrobial resistance has also been receiving increased recognition3. If healthcare-associated infections are reduced, then there is less need for prescribing antibiotics to patients, thus lowering their consumption and reducing the spread of resistant organisms. As it is generally recognized that 50-70% of healthcare-associated infections are transmitted by healthcare workers’ hands, hand hygiene with alcohol-based handrub is the primary line of defense against such transmission.

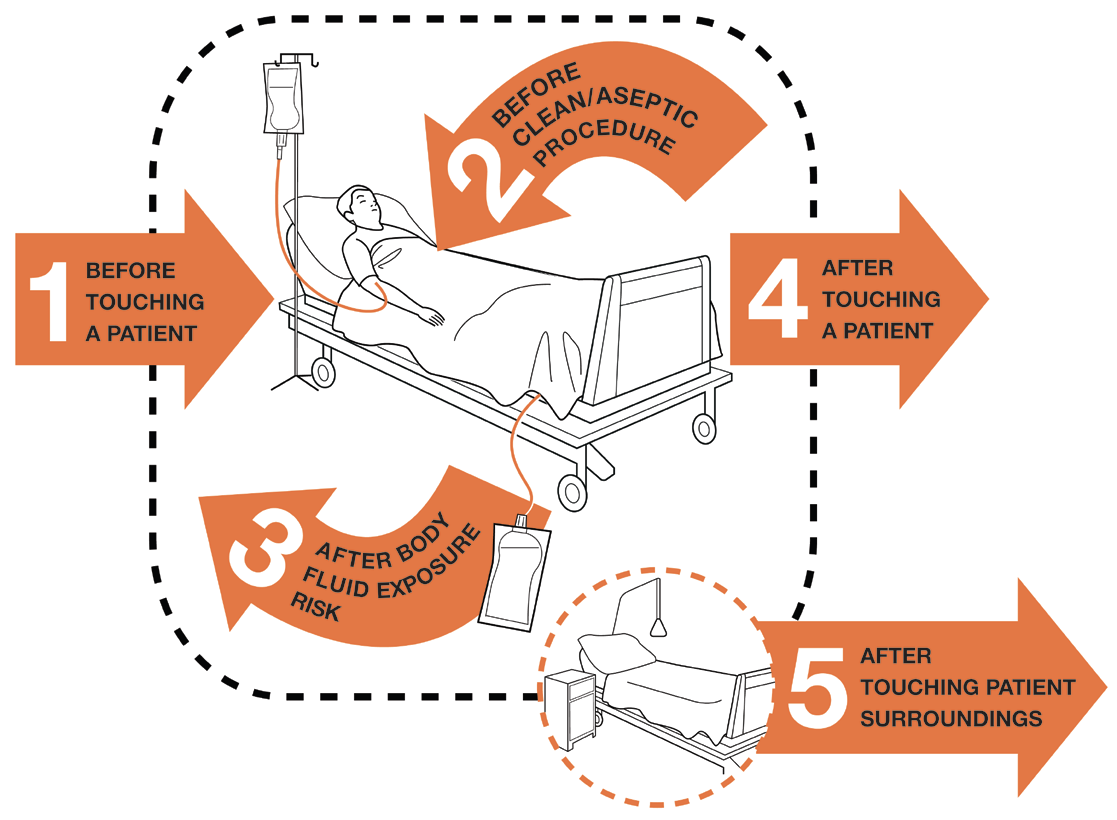

Figure 1. My five moments for Hand Hygiene in Health Care

There are numerous components that need to be in place for hand hygiene with alcohol-based handrub to be successful within a hospital, and for healthcare workers to be compliant with the World Health Organization (WHO) 5 Moments for hand hygiene (see Figure 1). While some are relatively easy physical measures to implement, others involve influencing the behavior of healthcare workers and are much more difficult to realize. The WHO developed a guide for implementation as a tool to facilitate hand hygiene adoption in healthcare settings around the world. This guide is constructed around the WHO multimodal strategy, which consists of system change, training and education, evaluation and feedback, reminders in the workplace, and institutional safety climate (see Figure 2)4.

The Multimodal Strategy

First and foremost, system change must be implemented by making sure that high-quality alcohol-based handrubs are available. This means they must have optimal antimicrobial efficacy, an optimal distribution system on hands, and be optimally placed in the healthcare setting at the point of patient care. The second part of the strategy consists of training and educating healthcare workers so that they understand the 5 Moments for when to use hand hygiene, how much alcohol-based handrub to use, and how to handrub. In order to make the training part of everyday practice, the WHO recommends evaluating and sharing performance feedback with the healthcare workers on how and when they performed hand hygiene, if the actions were sufficient, and if they were performed at the right time in order to foster a more complete understanding of the process. Reminders in the workplace are the fourth part and involve using tools such as posters or screen savers to keep the idea of performing hand hygiene in the minds of healthcare workers in everyday situations. The last part of the WHO multimodal strategy -“institutional safety climate”- is a bit less precise, as it concerns purely qualitative aspects of healthcare worker behavior and perception. According to the guide, it “refers to creating an environment and the perceptions that facilitate awareness-raising about patient safety issues while guaranteeing consideration of hand hygiene improvement as a high priority at all levels, including active participation at both the institutional and individual levels; awareness of individual and institutional capacity to change and improve (self-efficacy); and partnership with patients and patient organizations.”4

Unlike the other components that are comparatively straightforward to realize in the sense that there are set processes in place that can be adapted to any hospital, the institutional safety climate remains an intangible, albeit crucial, component to hand hygiene compliance.

The Quest for Excellence

We cannot improve the institutional safety climate without talking about culture change. We cannot talk about culture change without understanding the current culture and without talking about implementation science. We cannot talk about implementation science if we do not take into account how people think and work, and what is important to them. Institutional safety climate is inextricably linked to the notion of excellence and to the idea that healthcare workers embody their knowledge and feel that they have ownership of the culture of safety in a hospital. But what exactly is excellence, and how can we encourage it in practice?

Excellence in individuals, institutions, and companies is both a commitment and a process, and people need to make it theirs. Beyond the behavior of healthcare workers, hospitals need to help nurture environments that support staff and put patient safety at the center of the care they provide. Companies can excel by providing the best possible products that they can to the market, and help support the United Nations’ sustainable development goals as well as the WHO agenda towards quality universal health coverage. Excellence is a journey, and continuous improvement, innovation, and sustainability are key elements. Of course, the main framework is and will always be the science, the evidence. Healthcare workers need access to quality alcohol-based handrub, and they need to know how to use it. But practice is not theory, people are not rational, and hospitals are hectic and stressful places. A perfect one-size-fits-all solution does not exist because cultures, value systems, resources, working conditions, and education vary greatly among healthcare workers' populations. By connecting leadership, strategy, and culture in a way that makes sense to each individual institution’s needs, we can move towards excellence.

Leadership

Without the involvement of the WHO, hand hygiene could have never become a standard worldwide practice in hospitals this quickly. The story began in the mid-1990s, when researchers at the University of Geneva Hospitals were able to demonstrate that using alcohol-based handrub for hand hygiene was revolutionary in terms of its efficacy and the time that it saved. After being published in The Lancet in 20002, the “Geneva Model” for hand hygiene garnered worldwide attention and began to be implemented in institutions around the world5,6,7,8.

The WHO launched the World Alliance for Patient Safety in 20049, and soon after incorporated hand hygiene as the central part of its Clean Care is Safer Care campaign. They tested the implementation of the multimodal strategy in a quasi-experimental study in six countries with vastly different cultures and resources (Costa Rica, Italy, Mali, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia)10. The study proved successful worldwide across geographic regions, healthcare worker categories, and levels of development (see Figure 3). This study highlighted the importance of adaptation of the multimodal strategy to local resources and access to alcohol-based handrub, including the feasibility of producing alcohol-based handrub locally10,11,12.

In 2009, the updated version of the guidelines for the WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care was published, with particular focus given to the implementation of the multimodal improvement strategy. That same year, WHO started the SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands campaign, choosing the 5th of May as the international day for hand hygiene (in reference to the 5 moments for hand hygiene and the 5 components of the multimodal strategy)13,14.

In 2010, the WHO issued the Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework (HHSAF) as a tool for healthcare facilities to assess their level of success at implementing hand hygiene measures in their institutions15,16. This tool looks at specific indicators within each of the components of the multimodal strategy, and allows institutions to score themselves by the number of points obtained. The Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework then directs healthcare facilities to the appropriate WHO tools for improving their scores in specific areas15. The institutions with the highest scores globally then have the possibility to apply for the Hand Hygiene Excellence Award (HHEA; www.hhea.info)

To date, over 21,000 healthcare facilities have joined the WHO campaign for hand hygiene, and it is endorsed by national agencies as well as professional societies and private companies around the world13,17,18. The global implementation of hand hygiene has become the most successful WHO initiative ever undertaken, and currently, most of the world (over 140 countries) has signed the WHO pledge, officially committing to implementing hand hygiene and the WHO Guidelines at a national level19,20. Because of the work of the WHO and the ongoing commitment of healthcare facilities worldwide, hand hygiene is now a key indicator of the quality of healthcare systems around the world.

Beyond the global leadership of the WHO, it is important to note that leadership is also crucial at national, local, and institutional levels. Wards with a head nurse who is strong in infection prevention and control and champions of hand hygiene among the staff have a very different culture of compliance than those that do not. Each individual, no matter what their function, can be a champion of hand hygiene in their institution and can make a real difference in patient safety.

Strategy: Adapt to Adopt

The WHO multimodal strategy, 5 Moments for hand hygiene, and their associated tools are all part of the prerequisite strategy that was used for implementing the use of alcohol-based handrub in healthcare facilities worldwide. The tools promoted by the WHO can be adapted to different languages, cultural contexts, and available resources. The principle that ministries of health and hospitals can make these tools adapted to their needs is essential to their successful implementation21. In Japan, Hello Kitty has been used to teach hand hygiene; in other places, the color, order, language, and way of teaching were changed as well in order to adapt to local needs21. Some have tested interventions such as usable reminders when the healthcare worker enters or exits an area22. What remains most important is that institutions figure out what works for them, and that they do that.

Private companies have become an instrumental ally in helping countries and health facilities “adapt to adopt”. In 2012, the WHO launched the Private Organizations for Patient Safety (POPS), in an effort to encourage corporate social responsibility and harness the strengths of industry to improve the implementation of the WHO guidelines around the world18. These companies have the distinct advantage of being in the field on a daily basis and have a unique opportunity to drive excellence at the facility level.

Culture

The term “culture” is rather broad, yet relevant to each level of analysis. It can refer to a culture of excellence (or carelessness) within a specific institution, societal norms that impact alcohol-based handrub adoption in certain regions of the world, or the way that one can create change on a global scale. One example of this is the work done in the area of social innovation, by enabling the local production of alcohol-based handrub. This initiative is especially important for low-resource settings, where there is either not enough money or not enough of a robust infrastructure to buy and ship ready-made alcohol-based handrub internationally. Alcohol is easily produced from the byproducts of many of the already existing industries in the developing world, such as sugar cane, manioc, rice, potato, wood, or beets (see Figure 4). With the WHO guide to local production, individual companies and healthcare facilities can commit to producing high-quality, effective alcohol-based handrub themselves23.

One particular example of a successful local production initiative is the work of Saraya at the Kakira Sugar Works in Jinja, Uganda, which employs over 7,500 people. This social business was founded by Saraya in 2011, and it locally produces the highest quality alcohol-based handrub and distributes it to healthcare facilities. The project also aims to solve social issues by creating local jobs and developing itself as a sustainable business. At the beginning of the project, there were five Japanese employees from Saraya, and now there is only one Japanese manager left and 15 employees who are of local origin. Currently, the factory can produce up to 1,400L of ethanol per day (See Figure 5). Although the factory is not generating a profit, it is making a huge difference in the lives of the people living there. Importantly, this model remains quite unique today and deserves to be considered as a model to be reproduced wherever needed.

Ultimately, if our common goal is to save lives by reducing healthcare-associated infections, companies in this field are well-placed to have a high level of social awareness and responsibility. Saving and improving lives extends further than the hospitals that buy their products, and championing social innovation is a way for companies to be more than purely financially motivated entities. Ultimately, they can be just as successful or even more successful at improving lives by expanding their activities to the communities that need them the most.

Conclusion

Achieving success and striving for excellence is never a linear exercise. The story of implementing hand hygiene with alcohol-based handrub across the globe is one of immense importance, as well as one of dedication, passion, resilience, and adaptability. Although science and technology are at their core, bringing that science to a human element is incredibly complex, and there is not one universal right answer when it comes to implementation. In order for your own facility to achieve excellence in hand hygiene, it must incorporate elements of leadership, strategy, and culture. These three components encourage innovation, and others can benefit from that innovation anywhere in the world, whatever the available resources happen to be. Ultimately, excellence in hand hygiene is developing solutions that are scientifically sound and implementing them in a way that makes people care.

-

Publication Date:February 28, 2020

-

Category:Hand Hygiene

2020 Vol. 1

Other Articles in this volume

Other Hand Hygiene Articles

References

- World Health Organization. "Health care-associated infections FACT SHEET." (NA). Available at: https://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/gpsc_ccisc_fact_sheet_en.pdf (Accessed: 18th December 2018)

- Pittet, D. et al. "Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection Control Programme." Lancet 356, 1307–1312 (2000).

- World Health Organization. "Hand hygiene a key defence in Europe’s fight against antibiotic resistance." (2017). Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/antimicrobial-resistance/news/news/2017/05/ hand-hygiene-a-key-defence-in-europes-fight-against-antibiotic-resistance (Accessed: 15th December 2018)

- World Health Organization. "Guide to Implementation: A Guide to the Implementation of the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy." (2009). Available at: https://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Guide_to_ Implementation.pdf (Accessed: 18th December 2018)

- Grayson, M. L. et al. "Outcomes from the first 2 years of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative." The Medical Journal of Australia 195, 615–619 (2011).

- S. Fonguh, A. Uwineza, B. Catry, A. Simon & the national hand hygiene working group. "National campaigns to promote hand hygiene in Belgian hospitals: A continuous project." (NA) Available at: https://slideplayer.com/slide/12851324/ (Accessed: 18th December 2018)

- Magiorakos, A. P. et al. "Pathways to clean hands: highlights of successful hand hygiene implementation strategies in Europe." Eurosurveillance 15, 19560 (2010).

- Sheldon Stone et al. "Report to the Patient Safety Research Programme: on 'The National Observational Study to Evaluate the Cleanyourhands Campaign (NOSEC)' and 'The Feedback Intervention Trial (FIT)'." (2010).

- World Health Organization. "World Alliance for Patient Safety: The Launch of the World Alliance for Patient Safety, Washington DC, USA — 27 October 2004." (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/worldalliance/en/(Accessed: 15th October 2018)

- Allegranzi, B. et al. "Global implementation of WHO’s multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene: a quasi-experimental study." Lancet Infectious Diseases 13, 843–851 (2013).

- Allegranzi, B. et al. "Successful implementation of the World Health Organization hand hygiene improvement strategy in a referral hospital in Mali, Africa." Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 31, 133–141 (2010).

- World Health Organization. "Local production of WHO-recommended alcohol based handrubs: feasibility, advantages, barriers and costs." (2013). Available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/12/12-117085/en/ (Accessed: 30th August 2018)

- World Health Organization. "Web sites promoting WHO SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands." (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/SLCYH_support/en/ (Accessed: 31st August 2018)

- World Health Organization. "About SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands." (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/background/5moments/en/ (Accessed: 15th October 2018)

- World Health Organization. "WHO Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework." (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/hhsa_framework/en/ (Accessed: 15th October 2018)

- Stewardson, A. J., Allegranzi, B., Perneger, T. V., Attar, H. and Pittet, D. "Testing the WHO Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework for usability and reliability." Journal of Hospital Infection 83, 30–35 (2013).

- World Health Organization. "Support from WHO Member States and autonomous areas: Infection Prevention and Control." (2018). Available at: http://www.who. int/infection-prevention/countries/hand-hygiene/statements/en/ (Accessed: 15th October 2018)

- World Health Organization. "Private Organizations for Patient Safety (POPS)." (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/pops/en/ (Accessed: 16th December 2018)

- World Health Organization. "The First Global Patient Safety Challenge: ‘Clean Care is Safer Care’" (2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/clean_care_ is_safer_care/en/ (Accessed: 28th August 2018)

- Stewardson, A. J. & Pittet, D. "Historical Perspectives." in Hand Hygiene: A Handbook for Medical Professionals 8–11 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017). doi:10.1002/9781118846810.ch2

- TEDx Talks. Adapt to adopt | Didier Pittet | TEDxPlaceDesNations. (2016).

- Fakhry, M., Hanna, G. B., Anderson, O., Holmes, A. & Nathwani, D. "Effectiveness of an audible reminder on hand hygiene adherence." American Journal of Infection Control 40, 320–323 (2012).

- World Health Organization. "Guide to Local Production: WHO-recommended Handrub Formulations." Available at: https://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Guide_ to_Local_Production.pdf (Accessed: 18th December 2018)